An die Hoffnung op. 124

for alto (or mezzo-soprano) and orchestra

-

An die Hoffnung

Text: Friedrich Hölderlin

- -

- -

- -

1.

| Reger-Werkausgabe | Bd. II/6: Lieder mit Orchesterbegleitung, S. 2–33. |

| Herausgeber | Christopher Grafschmidt, Claudia Seidl. Unter Mitarbeit von Knud Breyer und Stefan König. |

| Verlag | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart; Verlagsnummer: CV 52.813. |

| Erscheinungsdatum | September 2023. |

| Notensatz | Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart. |

| Copyright | 2023 by Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart and Max-Reger-Institut, Karlsruhe – CV 52.813. Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. / Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. / All rights reserved. |

| ISMN | 979-0-007-30199-6. |

| ISBN | 978-3-89948-446-5. |

An die Hoffnung

Friedrich Hölderlin: An die Hoffnung, in:

id.: Taschenbuch für das Jahr 1805. Der Liebe und Freundschaft gewidmet, Friedrich Wilmans, Frankfurt am Main

Friedrich Hölderlin: An die Hoffnung, in: id.: Gedichte, Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig , p. 31–32.

Copy shown in RWA: DE, Meiningen, Meininger Museen, Rbü 140.

Note: Regers Exemplar in den Meininger Museen (Max-Reger-Archiv) ist nur auf den Seiten 30/31 und 32/33 aufgeschnitten, der Text An die Hoffnung ist mit Bleistift unterteilt.

Note: Als Abschluss der vierten Strophe hat Reger eine Zeile eingefügt: “o du Holde, Holde, dich, ja dich will ich finden”.

1. Composition and Publication

Before taking up his post in Meiningen, Reger had approached the genre of the orchestral song only tentatively. His Weihegesang (text by Otto Liebmann), written in 1908 for the University of Jena and accompanied only by a small wind band, featured a solo contralto but also a mixed chorus; in his Weihe der Nacht of 1911 (to a text by Friedrich Hebbel), the soloist’s voice was indeed borne by a symphony orchestra, but similarly required a male-voice choir.

When he was planning how to use his free time after his first season with the Meiningen Orchestra, Reger turned to his friend Karl Straube on 29 February 1912 with an urgent request, among other things, to procure him a “text for a ‘scene’ (recitative) and aria’ [sic] for contralto and orchestra”. (Postcard.) Just over a month later, Straube apparently sent him a volume of poems by Friedrich Hölderlin, published by Reclam. This provided him with the text for An die Hoffnung.1

Reger mentioned this new work by name for the first time on 19 April 1912,2 and in a letter of 28 April to his publisher Bote & Bock, he listed it among his new works for the coming autumn alongside his Konzert im alten Stil op. 123, the Romantische Suite op. 125 and his Römischer Triumphgesang op. 126. He asked them for a decision as to “which work I may give to C.F. Peters”. (Letter.)3 A few days later, Hugo Bock informed him that he could dispose of the orchestral song as he wished, and Reger subsequently offered it to Henri Hinrichsen, the owner of C.F. Peters, when they met in Leipzig on 9 May.

By this point, Reger had already begun work on An die Hoffnung. On 10 May he reported to his employer, Duke Georg, that while concluding his work on the Konzert im alten Stil he had “already sketched something new again […]. By 1 June, this work too will go to the printers” (letter)4. Less than two weeks later, “‘An die Hoffnung’ for contralto (mezzo-soprano) voice with orchestral or piano accompaniment is complete; it is a wonderful text by Fr. Hölderlin; the 28 pages of score are finished; now I still have to make the piano edition and remove any errors from the score, etc., which will take up to another 8 days of work.” (Brief vom 22. Mai 1912 an Herzog Georg II.)5.

It was Reger’s custom to adapt his texts repeatedly, to a greater or lesser degree, at the latest during the course of actually setting them to music. In An die Hoffnung, a key passage offers testimony to his intensive engagement with the text. At the close of verses three and four (of which the former flows into the latter), Reger takes the promise made a few lines earlier that “I shall seek you, my lovely, there in the silence” and uses varied repetition to turn it into an expression of heartfelt desire (before Figure 10): “O my lovely, my lovely, I shall find you, yes, you”.6

On 29 May 1912, Reger submitted the engraver’s copies of the work to his publisher C.F. Peters, suggesting that the orchestral parts should only be produced as lithographs, and pointing out, for example, that “the red notes in the vocal part (in the score and piano edition) […] must be engraved in small notes”. (Letter.)7 Since Reger had only asked for 500 marks – a sum that Hinrichsen himself regarded as too low – the latter reserved the right “to pay a further fee”, should the work “be a great success”. He observed that there was “at present a need for vocal works for solo voice and orchestra” (letter from Hinrichsen of 30 Mai 1912).

Reger confirmed the receipt of the proofs on 27 June, returned a corrected copy of the piano edition on 4 July, and handed over the corrected score to Hinrichsen in person on 11 July.8 He received the printed piano edition already by 13 July, and sent a copy to its dedicatee, Anna Erler-Schnaudt, along with the rehearsal plan for its first performance and a request for her to name other songs that she would like to sing. (Letter.) The first edition of the score reached him in mid-September.9 The piano edition in particular “proved relatively marketable: 200 more copies were printed in January 1913 and the same number again in November 1915, and 300 copies were reprinted on average every three years after Reger’s death”.10

2.

Translation by Chris Walton.

1. Early reception

The first performance took place on 12 October 1912 in Eisenach with Anna Erler-Schnaudt and the Meiningen Court Orchestra under Reger’s direction. It was awaited with “great excitement”, though the only reviews were in the local press. The critic of the Eisenacher Zeitung was full of praise: “Only a deeply sensitive composer could have chosen this text, which gives us a glimpse into the resigned, bleak world of Hölderlin’s thought. The poet, tormented by an unhappy passion, does not dare to believe that hope might be nearby to bring him earthly joys; he suspects that only death can offer him relief from earthly disharmony. […] A lengthy, grandly sombre orchestral introduction leads us into the ‘house of the mourner’; a desperate struggle and weary renunciation find expression here. This atmosphere continues in the first verse; in the second, the poet says that, although still here on earth, he already resembles the shades of the underworld. Strange harmonies, as if from another world, are able to paint for us a picture of the realm of shadows with just a few brush strokes; indeed, great concision and brevity are generally characteristic of this composition by Reger. In the third verse, a friendlier image comes to life: the poet seeks hope ‘in the green valley’, at a fresh spring. He is thus seeking comfort in Nature. This fresh spring is again depicted succinctly in the music. The most delectable passages in this work are to be found in the fourth verse, which depicts the invisible life of the night and the stars. The close, which expresses the poet’s readiness for death, is also extraordinarily effective. This work is a masterpiece of orchestral writing – I shall here mention only the use of the winds – and it is also striking for its mature, wise economy of means. We never encounter any outward effect here; this is genuine, interior music throughout, and this is why it has such a lasting impact.”1

After a further performance in Hildburghausen on 13 October, Richard Johne predicted that the work would enjoy a “triumphal procession through the concert halls”, because Reger “here elicits sounds that can touch every tender stirring of the spirit; the tone he strikes is given only to a divinely gifted genius. […] Only a truly poetic, heartfelt nature can move us so deeply.”2 Erler-Schnaudt’s contribution to the success of these concerts was honoured the next year, at Reger’s instigation,3 when she was awarded the honorary title of “Kammersängerin” to the ducal court of Saxe-Meiningen. She sang this work many times in the years thereafter, sometimes without Reger’s direct participation.

At a performance in Berlin on 28 December 1912 with Gertrud Fischer-Maretzki as soloist and the Blüthner Orchestra under Reger’s baton, the critics Max Chop and Wilhelm Altmann both drew attention to the “more passionately coloured”4 middle section of the work, which they deemed “relatively amiable” 5 in tone, though in Altmann’s opinion, its “fine orchestral tone-painting” rather suggested “renunciation, not hope”. Chop found that Fischer-Maretzki had sung “with a strange degree of restraint”. This was an impression that Erler-Schnaudt also seemed to convey to a certain extent when she sang the work in a concert in Bonn on 13 November 1913, and a local critic wrote: “In accordance with Reger’s desire, she studiously avoids all outward show and offers us the results of her long study of the work in an interiorised rendition of it.” 6

At the Bach-Reger Festival in Heidelberg on 24 June 1913, this work left the critic of the Heidelberger Zeitung “somewhat cold” because he did not like “this almost recitative-like, mostly chromatic, well-nigh psalmodising shape of the vocal line”. He added: “my opinion is not altered by the redemptive effect of the emergence of the vocal line from the gloom and its culmination in the major mode.”7 His colleague of the Heidelberger Tageblatt felt that Reger’s op. 124 seemed like a precursor to the Romantische Suite op. 125 that been heard just before it in the concert, “though this latter work is more beautiful, more lively, full of bigger breaths”.8)

Nor did An die Hoffnung meet with undivided approval at a performance given by Emmi Leisner on 8 January 1915 in Wiesbaden. The Rheinische Musik- und Theater-Zeitung noted that there had been “Great jubilation in the Kurhaus, where Max Reger conducted some of his latest compositions in person”, though he complained that “the basic mood” of An die Hoffnung “remained rather too whining”.9 The reviewer of the Wiesbadener Bade-Blatt was of a different opinion, however: “An atmospheric introduction begins, quivering with quiet melancholy, whose irresistible power compels the listener to attune his sensibility to the lamenting, comforting and hopeful words to which the human voice here lends eloquent expression. In magnificently colourful harmonies, the accompanying orchestra quite splendidly illustrates and intensifies the vocal line”.10

Willy von Beckerath expressed similar sentiments when recommending Gustav Ophüls to study this work: “It flowed from the most profound depths of Reger’s soul. Hölderlin’s wonderful text overlaps with a basic mood of the composer in an almost miraculous way. The result is a unity of text and music that I cannot imagine being achieved in a more consummate manner.”11

2.

Translation by Chris Walton.

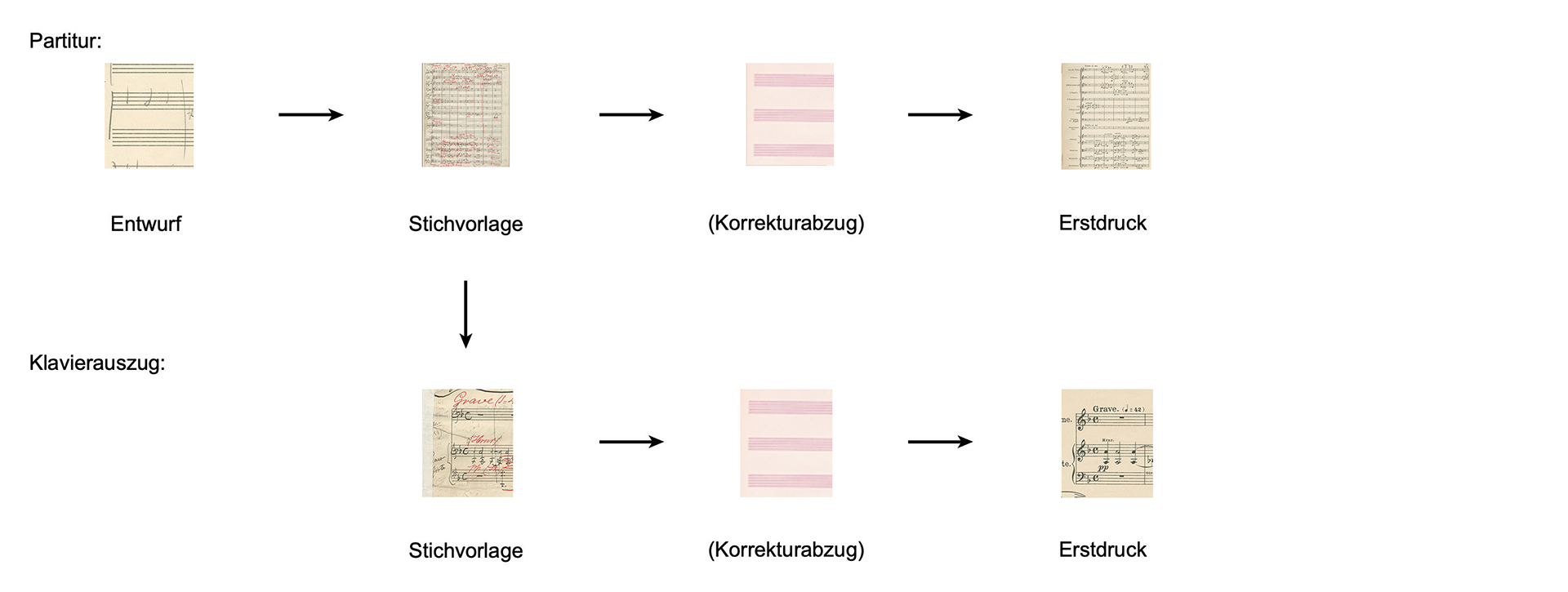

1. Stemma

2. Quellenbewertung

Der Edition liegt als Leitquelle der Erstdruck zugrunde. Als Referenzquellen wurden die Stichvorlage der Partitur sowie in wenigen Fällen Erstdruck und Stichvorlage des Klavierauszugs herangezogen. Der Entwurf spielte keine entscheidende Rolle.

3. Sources

- Entwurf

- Stichvorlage der Partitur

- Stichvorlage des Klavierauszugs

- Erstdruck der Partitur

- Erstdruck des Klavierauszugs

- Erstdruck der Orchesterstimmen

Object reference

Max Reger: An die Hoffnung op. 124, in: Reger-Werkausgabe, www.reger-werkausgabe.de/mri_work_00149.html, last check: 18th May 2024.

Information

This is an object entry from the RWA encyclopaedia. Links and references to other objects within the encyclopaedia are currently not all active. These will be successively activated.